Моисей Самуилович Вайнбер

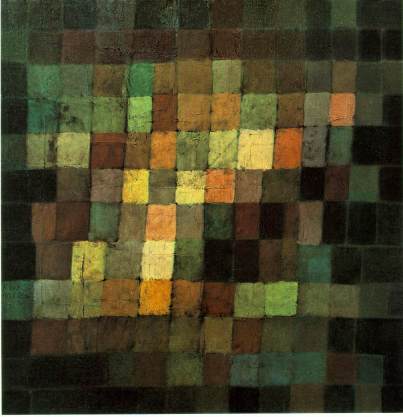

Light in the Dark

The Music of

Mieczyslaw Vainberg

When the history of 20th-century music is written in the next several hundred years, will it bear much resemblance to how we think of it now? My encounter with the works of Mieczyslaw Vainberg (1919-1996) makes me doubt that it will. So much music has been ignored or suppressed for aesthetic or political reasons during the 20th century that it will take some time for it to surface and receive a fair hearing. Enterprising record companies, such as Olympia, are in the vanguard of excavating our recent past, and their efforts are already shifting the perspective from which 20th-century music will be judged.

In an extraordinary feat of dedication, Olympia has released 16 CDs of Vainberg’s music. These discs, many of them Soviet-era recordings of live premiere performances, give a substantial representation of Vainberg’s enormous output. Vainberg composed 26 symphonies; seven concertos; 17 string quartets; 28 sonatas for various instruments; seven operas; several ballets; incidental music for 65 films; and many other works, including a Requiem.

One would think the sheer size of his output would command attention. Yet Vainberg is absent from every 20th-century musical reference work I have checked and receives a paltry two paragraphs in The New Grove Dictionary (under Vaynberg). What deepens the mystery of this neglect is that a number of his works are masterpieces that belong in any evaluation of 20th-century music. Thanks to Olympia, and a few other labels, a reevaluation can now begin.

The story of Vainberg’s neglect is a history of the 20th century at its worst, encompassing both the Nazi and Soviet tyrannies. Vainberg was born in Warsaw, where his father worked as a composer and violinist in a travelling Jewish theater. Vainberg made his debut as a pianist at the age of ten. Two years later, he became a pupil at the Warsaw Conservatory. In 1941, his entire family was burned alive by the Nazis. As a refugee, Vainberg fled first to Minsk and then, in advance of the invading Nazi armies, to Tashkent. In 1943, he sent the score of his First Symphony to Shostakovich, who was so impressed that he arranged for Vainberg to be officially invited to Moscow. For the rest of his life, Vainberg remained in Moscow, working as a freelance composer and pianist. He and Shostakovich became fast friends and colleagues.

Vainberg was to discover that anti-Semitism was not only a Nazi specialty. In 1948, at the Soviet Composers Union Congress, Andrei Zhdandov, Stalins cultural henchman, attacked formalism and cosmopolitanism, which were code words for Jewish influences. During the meeting, Vainberg received news that his father-in-law, the most famous Jewish actor in the Soviet Union, Solomon Mikhoels, had been murdered (as it was later learned, on direct orders from Stalin). At first, Vainberg, who always refused to join the Communist Party, seemed safe and was even praised by the newly elected head of the Composers Union, Tikhon Khrennikov, for depicting the shining, free working life of the Jewish people in the land of Socialism.

Nonetheless, Vainberg was arrested in January 1953 for Jewish bourgeois nationalism, on the absurd charge of plotting to set up a Jewish republic in the Crimea. This event took place in the midst of the notorious Doctors Plot, used by Stalin as pretext for another anti-Semitic purge. Seven of the nine Kremlin doctors were Jewish. One of them was Miron Vovsi, the uncle of Vainberg’s wife. Vovsi was executed [see Note 1]. Speaking of Vainberg’s arrest, his wife Natalya said, to be arrested in those times meant departure forever. Expecting her own arrest, Natalya arranged for the Shostakovich’s to have power of attorney over her seven-year-old daughter so that the girl would not be sent to an orphanage.

According to Olympias consultant for its Vainberg series, Tommy Persson, a Swedish friend of the composer and his family, Vainberg thought he would not survive his internment, if only due to his poor health at the time. In -30 ÞC weather, he was taken outside in only his prison garb and shorn of all his hair. He was interrogated and allowed no sleep between 11:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. In an act of great courage, Shostakovich sent a letter to the chief of the NKVD (the predecessor to the KGB), Lavrenti Beria, protesting Vainberg’s innocence. But it was only Stalins death in March of that year that opened the prison gates for Vainberg and many others. To celebrate his release, the Shostakoviches and Vainberg’s held a dinner party at which they burned the power of attorney papers.

These events are worth recounting in detail because of the attitude that Vainberg took toward them and that is, in turn, reflected in his music. He seemed to regard his imprisonment with some diffidence. Of the Stalinist peril, he said, It wasnt a sword of Damocles, because they hardly locked up any composerswell, except meand they didnt shoot any either. I really cant claim, as other composers do, that I have been persecuted. Vainberg must have possessed an extraordinary spiritual equanimity to say such a thing.

What sort of music does one write in the face of the horrors of Nazi genocide, World War II, and the Gulag, especially if one has been victimized by all three? In his December 19 article on 20th-century music after the war, New York Times writer Paul Griffiths opined that since what had recently happened was inexpressible, the only appropriate course was to express nothing. And indeed that was the course chosen by many composers in their increasingly violent and abstract works. The more repugnant the world, the more abstract the art.

The only problem with this approach is that the art it produces is itself repugnant because it is inhuman. Vainberg chose another course. It was neither one of denial, nor one of submission to the Soviet mandate to write happy-factory-worker music. He said, Many of my works are related to the theme of war. This, alas, was not my own choice. It was dictated by my fate, by the tragic fate of my relatives. I regard it as my moral duty to write about the war, about the horrors that befell mankind in our century.

Yet Vainberg was able to address these issues with the same spiritual equanimity with which he regarded his imprisonment. Though his music is certainly passionate, he seems to have been able to recollect the most horrible things in tranquility. Since so little is known about Vainberg, it can only be a guess as to how he was able to do this.

In conversation with Persson, I was told, Vainberg could always see the bright light in dark circumstances. What was the source of this perspective? Much is revealed in a remark from an interview Vainberg gave after the collapse of the Soviet Union: I said to myself that God is everywhere. Since my First Symphony, a sort of chorale has been wandering around within me. If God is everywhere, then there is still something to say. Vainberg found the means to say it in music of great passion, poignance, power, beauty, and even peace.

Vainberg’s musical language may be another reason for his neglect. He frequently sounds exactly like Shostakovich, and that similarity will be the first thing likely to strike any listener. Vainberg embraced the similarity, declaring unabashedly, I am a pupil of Shostakovich. Although I never took lessons from him, I count myself as his pupil, his flesh and blood. In turn, Shostakovich called Vainberg one of the most outstanding composers of the present day.

Shared stylistic traits are immediately recognizable in the frequent deployment of high string and horn registers, and the sometimes-obsessive use of themes. Like Shostakovich, Vainberg wrote open, expansive music of big gestures and extraordinarily long-lined melodies. Both composers were classical symphonists who wrote essentially tonally oriented music.

Though ridiculed as a little Shostakovich, Vainberg actually was sometimes the one influencing Shostakovich, rather than the other way around. Vainberg seems to have been the primary source of the Jewish musical influences in Shostakovich’s works, most certainly in Shostakovich’s song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. And who was influencing whom in 1962, when Shostakovich composed the Thirteenth Symphony, Babi Yar, about Nazi atrocities against Soviet Jews, and Vainberg wrote his Sixth Symphony memorializing children who were murdered or orphaned? So close were the two composers that they observed a steadfast practice of playing for each other every new work as soon as it was finished. Also, each composer, in tribute, liberally quoted the others works.

However, there are defining differences. Vainberg wrote with irony (and sometimes even humor) but without Shostakovich’s sardonic bombast and cutting edge. He held his musical onslaughts more in check. Vainberg’s music can be very turbulent and bleak, but the bleakness and turbulence are not unremitting. They are, in fact, relieved by a fundamental optimism in Vainberg’s outlook that clearly differentiates him from Shostakovich. The frequent diminuendos with which Vainberg ends his works do not signify resignation or death but peace.

Vainberg was more a romantic than Shostakovich; he wore his heart more on his sleeve. As a result, his writing is more florid, though his symphonic structures remained more classical than those of Shostakovich. In his later years, Vainberg’s music, as evident from his last several chamber symphonies, even increased in lyrical beauty and contemplative value.

The similarities with Shostakovich may also cause one to overlook Vainberg’s own significant melodic gift and his extraordinary ability to develop his themes, which cannot be the product of imitation. Vainberg knew how to take a simple idea and build it into a major edifice. There is also the matter of his remarkable fluency. Vainberg’s music seems to burst forth from such an abundance of ideas that one can only assume that music was his natural language.

Russian composer Boris Tishchenko said of Vainberg, The music seems to flow by itself, without the slightest effort on his part. This fluency, he said, allowed Vainberg to make a game of music making. But even so, this game never becomes simply amusement. In every composition, one can hear his pure voice, the voice of the artist, whose main goal is to speak out in defense of life.

In The New Grove, Boris Schwarz calls Vainberg a conservative modernist. The reverse would be more accurate. In musical idiom, he was a modern conservative. Besides Shostakovich, other palpable influences are Prokofiev, Stravinsky, and especially Mahler. Vainberg worked with traditional harmonic and tonal expectations and rarely failed to meet them in satisfying and novel ways. He could sustain a sense of expectancy over long spans of time with vast melodic and contrapuntal structures.

The symphonies are often masterful in their thematic coherence. The whole of Symphony No. 19, for example, is developed out of its gorgeous opening theme over the course of more than half an hour. Although the symphony is subtitled The Bright May and has extramusical associations with the end of the war, it is musically satisfying in the profoundest way. Vainberg’s music is also highly variegated, encompassing calliope music, circus marches, Jewish and Moldavian folk song and dance, Shostakovich-like onslaughts, and extremely moving Malherian adagios.

The Symphony No. 2, for strings alone, written in 1945 to 1946, should serve as fair warning to those who wish to tie this composers work to his biography. In the wake of the wars devastation, Vainberg produced a meltingly lovely, thoroughly charming, and relatively untroubled work. More than 40 years later, Vainberg added timpani to strings to produce his Chamber Symphony No. 2, another completely beguiling, classically oriented, if somewhat more weighty work. These are entrancing pieces.

Symphony No. 4 has immense propulsive drive, an engaging telegraphic theme, and wistful Stravinskian interludes. It is coupled on an Olympia CD with Vainberg’s Violin Concerto, a work of the first rank, charged with breathtaking vitality. Shostakovich said, I remain very impressed with the Violin Concerto by M.S. Vainberg…. It is a fabulous work. Though the Soviet-era recordings leave something to be desired, the quality of this music and the outstanding performances are thoroughly winning. If you are not engaged by these works, you need proceed no further.

Of Vainberg’s Sixth Symphony, Shostakovich exclaimed, I wish I could sign my name to this symphony. This is the work through which I first became acquainted with Vainberg on a now-deleted Jerusalem Records CD, appropriately coupled with Shostakovich’s From Jewish Folk Poetry (curiously, the two works share the same opus number, Op. 79).

The symphony begins with a hauntingly beautiful trumpet theme, which recurs and is developed throughout. Several of its movements include a childrens choir. Despite its gruesome subject matter, the murder of children, this ultimately affirmative work is a moving example of Vainberg’s ability to recollect in tranquility. Only someone secure in faith and hope could treat this agonizing subject matter in this way. The closing line of the text is: There will be sunshine again and the violins will sing of peace on earth.

The Symphony No. 12, dedicated to the memory of Dmitri Shostakovich (and here conducted by his son ,Maxim) is a poundingly ferocious and poignant piece. It is magnificent music, but not for the faint of heart. The remarkable first movement, close to 20 minutes long, exhibits Vainberg’s ability to move seamlessly from angry outbursts to lyrical introspection. This is a stunning work.

The Symphony No. 19, The Bright May, is music of a man who more than simply survived and who did not return empty-handed from the hell through which he lived. An incredibly long and elegiac melodic line of great beauty begins and almost continuously winds its way through this single-movement masterpiece, which ends in a most poignant way. May may be bright, but it is also haunted. Along with the Sixth Symphony, this is perhaps Vainberg’s most moving work; he certainly wrote nothing more beautiful.

The Piano Quintet demonstrates Vainberg’s prowess with chamber music, and almost equals in brilliance and vitality Shostakovich’s great Piano Quintet.

The lovely Childrens Notebooks for piano proves that Vainberg was a master miniaturist as well as a great symphonist. His abundant charm and humor are evident here.

(…)

After a life of much pain, Vainberg spent his last several years in bed suffering from Crohns disease. On January 3, 1996, less than two months before his death on Ferbruary 26, he was baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church, one final act by a man who could always see the bright light in dark circumstances.

Courtesy of Robert R. Reilly (c)

Mieczysław Weinberg, piano sonata No.6, op. 73 (1960)

Мечислав (Моисей) Вайнберг, шестая соната, соч. 73 (1960)

I. Adagio

Mieczysław Weinberg (Moisei Vainberg)

(1919 – 1996)

Mieczysław Weinberg was one of the twentieth century’s most powerful and prolific composers, and one of its least well known, certainly outside of his adoptive Russia. His death in Moscow on 26 February, 1996, at the age of 76, brings to an end to a life that was far from easy but which was borne with the fortitude that gives his music its toughness and strength.

Weinberg was born on 8 December 1919 in Warsaw into a musical family: his father was a composer and violinist in a Jewish theatre there. He made his first public appearance as a pianist at the age of ten, and two years later became a student at the Warsaw Academy of Music, then under the direction of Karol Szymanowski, where he took piano lessons from Josef Turczynski. His graduation in 1939 was soon followed by Hitler’s invasion: when his entire family was killed, burned alive, Moisei fled eastwards, taking shelter first in Minsk, where he studied composition with Vassily Zolotaryov. Two years later, as Hitler now pushed into Russia, Weinberg again had to flee, this time finding work at the opera house in Tashkent, in Uzbekistan. It was there, in 1943, that he took the action that was perhaps to be the most decisive in his life: he sent the manuscript of his newly completed First Symphony to Dmitri Shostakovich in Moscow. Shostakovich’s response was typically helpful and immediate: Weinberg received an official invitation to travel to Moscow, where he was to spend the rest of his life, living largely by his compositions, though he also made many appearances as a pianist. One of the most prestigious was when, in October 1967, with Vishnevskaya, Oistrakh and Rostropovich, he played in the first performance of Shostakovich’s Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok, replacing the ailing composer. And when Shostakovich presented his latest works to the Composers’ Union and to the Soviet Ministry of Culture, it was generally in four-hand versions in which Weinberg was his habitual accompanist (in 1954, for example, they recorded the Tenth Symphony at the piano – a document of immense importance which has appeared in the West on LP and which ought now to be resuscitated on CD).

Having only just escaped the Nazis with his life, Weinberg was not to find matters much easier under Stalin. During the night of 12 January 1948 (the day before the opening of the infamous “Zhdanov” congress at which Shostakovich, Serge Prokofieff and several other composers were denounced as “formalists”), Solomon Mikhoels, Weinberg’s father-in-law and the perhaps the foremost actor in the Soviet Union, was murdered on Stalin’s orders, an early victim of the anti-Semitic campaign that was to be a feature of his last years in power. When, in February 1953, Weinberg himself was arrested, it seemed that he, too, might “disappear”; fortune intervened and Stalin’s death on 5 March removed the imminent danger. (In the meantime Shostakovich had acted true to form, taking the step, one of almost foolhardy generosity and courage, of writing to Stalin’s police chief Beriya to protest Weinberg’s innocence.) A month later Mikhoels was posthumously rehabilitated in the Soviet press, and soon after Weinberg himself was released.

Weinberg’s association with Shostakovich was not based only on mutual personal esteem. Shostakovich often spoke very highly of Weinberg’s music (calling him “one of the most outstanding composers of the present day”); he dedicated his Tenth String Quartet to him; and in February/March 1975, although terminally ill (he was to die on 9 August), he found the energy to attend all the rehearsals for the premiere of Weinberg’s opera The Madonna and the Soldier. Weinberg’s identification with Shostakovich’s musical language was such that to the innocent ear the best of his own music might also pass muster as very good Shostakovich. Weinberg was quite unabashed, stating with unsettling directness that “I am a pupil of Shostakovich. Although I have never had lessons from him, I count myself as his pupil, as his flesh and blood”. But there is much more to Weinberg than these external similarities of style, although his music – some of which achieves greatness – has yet to have the exposure that will allow his individuality to be fully recognised. It also embraces folk idioms from his native Poland, as well as Jewish and Moldavian elements; and towards the end of his career he found room for dodecaphony, though usually set in a tonal framework. His evident taste for humour, from the light and deft to biting satire, was complemented by a natural feeling for the epic: his Twelfth Symphony, for instance, dedicated to the memory of Shostakovich, effortlessly sustains a structure almost an hour in length; and Symphonies Nos. 17, 18 and 19 form a vast trilogy entitled On the Threshold of War.

The list of Weinberg’s compositions is enormous and deserves serious investigation both by musicians and record companies: there are no fewer than 26 symphonies (the last to be completed, Kaddish, is dedicated to the memory of the Jews who perished in the Warsaw Ghetto, Weinberg donating the manuscript to the Yad va-Shem memorial in Israel; the twenty-seventh was finished in piano score though not fully orchestrated); two sinfoniettas; seven concertos (variously for violin, cello, flute and trumpet); seventeen string quartets; nineteen sonatas for piano solo or in combination with violin, viola, cello, double-bass or clarinet; more than 150 songs; a Requiem; and an astonishing amount of music for the stage – seven operas, three operettas, two ballets, and incidental music for 65 films, plays, radio productions and circus performances.

Weinberg was never a Party member, although he turned in his fair share of celebratory “socialist realist” commissions. But the horrors he had lived through underlined his genuine antipathy to war, which was far from the empty harrumphing of the Soviet peace movement – it can be heard in (for example) how he treats the theme of death in his passionately humanist Sixth Symphony, to be found on one of four discs of Weinberg’s music released by the British company Olympia towards the end of the composer’s life (more releases are planned, apparently).

He spent his last days confined to bed by ill health, often in considerable pain and afflicted by a deep depression occasioned by the wholesale neglect of his music – an unworthy end to a career the importance of which has yet to be recognised. The news that a trust has been formed to promote his music may be the first sign that a revival of interest is at hand. Not before time.

Courtesy of Martin Anderson, 1996

.

.

Claes Gunnarsson, Svedlund, Göteborgs Symfoniker

Adagio • 7:20 Moderato – Lento • 12:59 Allegro – Cadenza. L’istesso tempo, molto appassionato – Andante – Allegro – Andante • 21:42 Allegro – Adagio – Meno mosso

.

Please note also : http://claude.torres1.perso.sfr.fr/Vainberg/WeinbergDiscographie.html

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.