.

The term “Gharana” comes from a Hindi word “Ghar” which means a house. “Gharana” in social context refers to a family staying in the house. Since families may stay in the house for generations, the common skills and traits of the members of the family and rituals and traditions followed by the family, become characteristics of a Gharana. The word “Gharana” in Hindustani Classical Music bears a special connotation – adherence to a comprehensive musicological ideology. Simply put it essentially refers to the style, of singing or playing an instrument, of the founder and other stalwarts of the Gharana. However, the word style, as applicable to vocal form, can be broken down further to include a number of characteristics of presentation of a Raga, such as, open voice using akar, clarity of notes, development and elaboration of a Raga, stress on breath control, rhythmplay, use of boltans and dancelike grace in Sargams, exquisite compositions and so on.

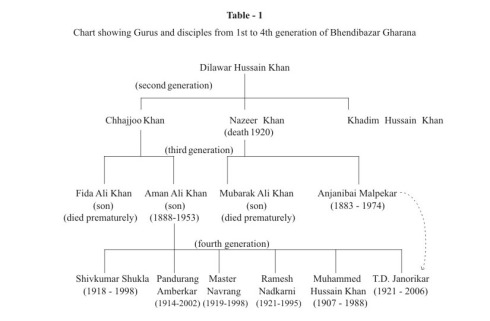

In the context of Bhendibazaar Gharana, the lineage can be traced to Ustad Dilawar Hussain Khan. His three sons, Ustad Chhajjoo Khan, Ustad Nazeer Khan and Ustad Khadim Hussain Khan (the Founders of Bhendibazaar Gharana) shifted in the year 1870 from Bijnaur, near Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh to Mumbai. Their brother Vilayat Hussain used to stay in an area called “Bhendibazaar” . The area “Bhendibazaar” is located close to the Fort area, the commercial centre of Bombay (now Mumbai). The locality close to the Fort area was referred to as “Behind the bazaar” by the British, which in local language came to be known as Bhendibazaar. The triumvirate had received training in music, initially from their father, Ustad Dilawar Hussain Khan, and later from Inayat Hussain Khan of Rampur Sahaswan Gharana and from Ustad Inayat Khan of the Dagar Gharana. The three brothers developed their own style and gained reputation as singers from “Bhendibazaar” and their style was called “Bhendibazaar Gayaki”.

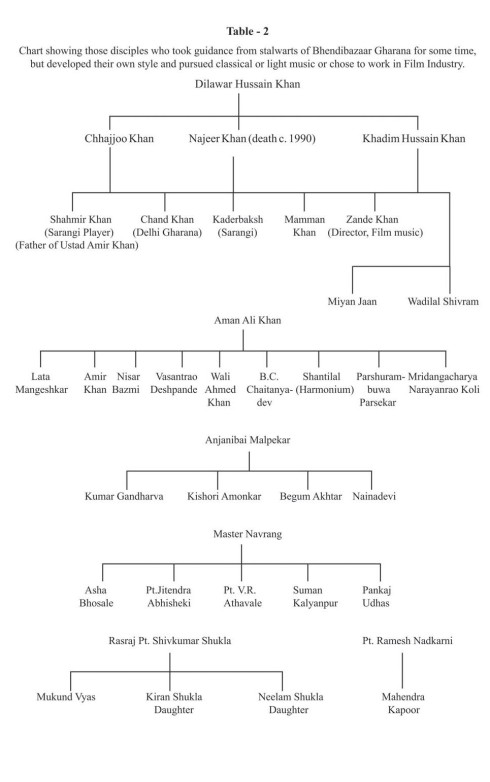

The Bhendibazaar Gayaki presented a novel approach in presentation of a raga and the impact on listeners and other musicians was so great that many stalwarts of other Gharanas and budding musicians preferred to take training; for example, Ustad Shahmir Khan (father of Ustad Amir Khan), Ustad Amir Khan himself, Ustad Chand Khan, Kader Baksh, Ustad Mamman Khan, Ustad Zande Khan, Lata Mangeshkar, Pandita Kishori Amonkar, Pt. Kumar Gandharva, Begum Akhtar, Naina Devi, Pt. Jitendra Abhisheki, Pt.Vasantrao Deshpande, Asha Bhosale, Mahendra Kapoor, Manna Dey. The biographies of the founders and other exponents of the Gharana are included in the next page. In this page, we shall see the information of Guru- Shishya parampara condensed in three lineage charts as per details given below:

.

.

.

.

.

.

The term “Gharana” comes from a Hindi word “Ghar” which means a house. “Gharana” in social context refers to a family staying in the house. Since families may stay in the house for generations, the common skills and traits of the members of the family and rituals and traditions followed by the family, become characteristics of a Gharana. The word “Gharana” in Hindustani Classical Music bears a special connotation – adherence to a comprehensive musicological ideology. Simply put it essentially refers to the style, of singing or playing an instrument, of the founder and other stalwarts of the Gharana. However, the word style, as applicable to vocal form, can be broken down further to include a number of characteristics of presentation of a Raga, such as, open voice using akar, clarity of notes, development and elaboration of a Raga, stress on breath control, rhythmplay, use of boltans and dancelike grace in Sargams, exquisite compositions and so on.

In the context of Bhendibazaar Gharana, the lineage can be traced to Ustad Dilawar Hussain Khan. His three sons, Ustad Chhajjoo Khan, Ustad Nazeer Khan and Ustad Khadim Hussain Khan (the Founders of Bhendibazaar Gharana) shifted in the year 1870 from Bijnaur, near Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh to Mumbai. Their brother Vilayat Hussain used to stay in an area called “Bhendibazaar” . The area “Bhendibazaar” is located close to the Fort area, the commercial centre of Bombay (now Mumbai). The locality close to the Fort area was referred to as “Behind the bazaar” by the British, which in local language came to be known as Bhendibazaar. The triumvirate had received training in music, initially from their father, Ustad Dilawar Hussain Khan, and later from Inayat Hussain Khan of Rampur Sahaswan Gharana and from Ustad Inayat Khan of the Dagar Gharana. The three brothers developed their own style and gained reputation as singers from “Bhendibazaar” and their style was called “Bhendibazaar Gayaki”.

The Bhendibazaar Gayaki presented a novel approach in presentation of a raga and the impact on listeners and other musicians was so great that many stalwarts of other Gharanas and budding musicians preferred to take training; for example, Ustad Shahmir Khan (father of Ustad Amir Khan), Ustad Amir Khan himself, Ustad Chand Khan, Kader Baksh, Ustad Mamman Khan, Ustad Zande Khan, Lata Mangeshkar, Pandita Kishori Amonkar, Pt. Kumar Gandharva, Begum Akhtar, Naina Devi, Pt. Jitendra Abhisheki, Pt.Vasantrao Deshpande, Asha Bhosale, Mahendra Kapoor, Manna Dey

Nuances of Bhendi Bazaar Gharana Gayaki

Nuances of Gayaki include the following prominent characteristics :

1. Akar sung in open voice,

2. Improvisation of the raga (alap, taan and sargam) based on Khandmer principle, i.e. various combinations of a given set of notes to bring out beauty and melody of the Raga,

3. Presentation in Madhya laya (medium tempo), and madhyadrut laya (medium fast tempo),

4. Melodious smooth meends with breath control,

5. Forceful Gamak taans, sapat taans and satta taans,

6. Presentation of Bandishes having delightful mixture of shabda, soor and laya (lyrics, notes and tempo),

7. Dance oriented structure of singing of sargams (singing complex combinations of solfa syllables in harmony with their designated pitches),

8. Individualistic and beautiful rhythmplay,

9. Inclusion of some melodious ragas of Karnatak Music, such as Hamsdhwani, Nagaswarawali, Pratapwarali.

* * * * * *

While a massive redevelopment project is underway at Bhendi Bazaar, a little known fact about the area is its rich contribution to Hindustani classical music

While all this is known and often talked about, a little known fact about the area is its rich contribution to Hindustani classical music. It was in 1890 that Bhendi Bazaar Gharana was founded in Mumbai by three brothers Ustad Chhajjoo Khan, Ustad Nazeer Khan and Ustad Khadim Hussain Khan, who hailed from Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh.

My mother, Late Mandakini Gadre, was a disciple of Master Navrang Nagpurkar, who was a leading disciple of Ustad Aman Ali Khan, the doyen of Bhendi Bazaar Gharana. I chose Bhendi Bazaar Gharana as the subject of the web site as my mother learnt music from Master Navrang, a maestro of the Bhendi Bazaar Gharana.

I strongly felt that artistes of the past era, of Bhendi Bazaar Gharana who had devoted their whole life to mastering, presenting and teaching music are forgotten today.The website provides information about Bhendi Bazaar Gharana, its guru-shishya parampara, some live recordings of some stalwarts from the Gharana.

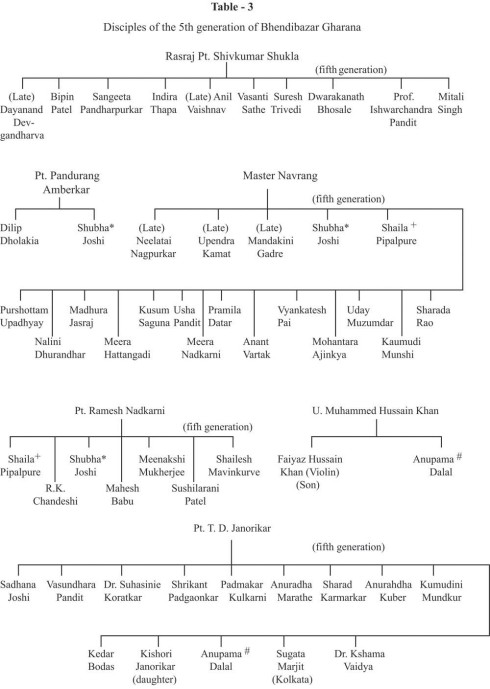

This treasure, if not preserved now, may be lost forever and will not be available to music lovers and students in future.” Highlighting various features of the website, Gadre added, “The website, which was launched in 2009 has nearly 250 Bandishes composed by Ustad Aman Ali Khan and other disciples including Pandit Shivkumar Shukla, Pandit Pandurang Amberkar, Master Navrang, Pandit Ramesh Nadkarni. There are Bandishes sung by disciples of the present generation.”

Forgotten

While Hindustani classical music has been dominated by other Gharanas like Kirana Gharana, Agra Gharana and so on, many feel that Bhendi Bazaar Gharana is a forgotten chapter and barely finds a mention in the Indian music scene. Said Suhasini Koratkar, currently one of the oldest members from the Bhendi Bazaar Gharana, based in Pune, “The problem with this Gharana was the death of many of its stalwarts before time.

Ustad Aman Ali Khan passed away quite early. The singers from this Gharana were not very much into performing at concerts. They used to teach their pupils and they were happy doing that. They considered that music was for spiritual purposes and not for sale.

This is probably one of the reasons why this Gharana did not become so popular.” Koratkar (67) recollects days when she started learning music under Pandit TD Janorikar in Pune, “My father loved Shastriya Sangeet and this is why he insisted that I start learning under Janorikar ji.

It was during his time that the Gharana flourished. He knew that for a Gharana to flourish it is important that people should be made aware of it. Hence he performed at a lot of concerts. After intensive practice for 7-8 years we too started performing at various concerts.

We wanted to keep the Gharana alive. My guru passed away in 2006. But I continued the sammelan pratha.” Koratkar worked as the Director of Programme (Music) at the All India Radio (AIR) in Delhi. “I started organising various sammelans in Delhi so that people could know about this Gharana,” she said.

Work

Another problem with this Gharana was absence of any written documents or books that talk about the Gharana and its distinguishing features. “It was the oral tradition followed by gurus and this is how knowledge was passed on to the disciples.

It is now that efforts are being made to document its history, origin, etcetera,” said Koratkar. With a handful of practitioners remaining, music lovers are not too optimistic about the future of the Bhendi Bazaar Gharana. Said Meenaxi Mukherji from Andheri (W), a singer who has been associated with the Gharana for almost 25 years, “What is required is a more coordinated effort by the singers who come from this Gharana.

Effort at an individual level will not be of much help. But a bigger project with help pouring in from various people will help resurrect this Gharana and make it popular. Otherwise, I think that the Gharana might soon become history.” Mukherji also laments the fact that, “in this day and age students look for quick money and fame. It is not just an art.

It is more of an aradhna (worship)–a way to reach the divine. After a year or two, students insist that they want to perform at concerts. There is also no money in this field. This is another reason why many shy away to take up classical music as a career.” Kedar Bodos, a classical singer based in Goa, concurs. “There is lack of patience among students. Their taste, in terms of music too is changing,” said Bodos who has trained in five different Gharanas including Bhendi Bazaar.

Bollywood connection

Lata Mangeshkar and Manna Dey learnt from Ustad Aman Ali Khan; Asha Bhosale and Pankaj Udhas from Master Navrang and Mahendra Kapur from Pandit Ramesh Nadkarni.

Unique

Nuances of Bhendi Bazaar Gayaki include the following prominent characteristics

* Improvisation of the raga (alap, taan and sargam) based on Khandmer principle, i.e. various combinations of a given set of notes to bring out beauty and melody of the Raga

* Presentation in Madhya laya (medium tempo), and madhyadrut laya (medium fast tempo)

* Inclusion of some melodious ragas of Karnatak Music, such as Hamsdhwani, Nagaswarawali, Pratapwarali.

History

In the context of Bhendi Bazaar Gharana, the lineage can be traced to Ustad Dilawar Hussain Khan. His three sons, Ustad Chhajjoo Khan, Ustad Nazeer Khan and Ustad Khadim Hussain Khan (the Founders of Bhendi Bazaar Gharana) shifted in the year 1870 from Bijnaur, near Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh to Mumbai.

Their brother Vilayat Hussain used to stay in an area called “Bhendi Bazaar” . The area “Bhendi Bazaar” is located close to the Fort area, the commercial centre of Bombay (now Mumbai). The locality close to the Fort area was referred to as “Behind the bazaar” by the British, which in local language came to be known as Bhendi Bazaar.

The triumvirate had received training in music, initially from their father, Ustad Dilawar Hussain Khan, and later from Inayat Hussain Khan of Rampur Sahaswan Gharana and from Ustad Inayat Khan of the Dagar Gharana. The three brothers developed their own style and gained reputation as singers from “Bhendi Bazaar” and their style was called “Bhendi Bazaar Gayaki”.

(Courtesy of Sudeshna Chowdhury)

* * *

Moradabad, a small town in Uttar Pradesh has been one of the heartlands of Hindustani classical instrumental music. Many senior Ustads have mastered the art of Sarangi, Tabla, Been and even vocal music from this gharana. How can one forget the legendary tabla player Ahmad Jaan Tirakhwa saab and great vocalists Ustad Chhajju Khan saab and Ustad Tajjammul khan saab who belong to this gharana? Murad ali belongs to the sixth generation of musicians from his family which has been serving music for the last 250 years. His grandfather Ustad Saddique Ahmad Khan saab and his father Ustad Ghulam Sabir khan saab need no introduction to the world of Hindustani classical music. One of the biggest assets of Moradabad gharana , unlike many other gharanas, is each and every musician is trained in both vocal and instrumental styles of performing. So a sarangi player also makes for a great vocalist and vice versa.

Moradabad gharana is also famously known as the ‘Bhindi bazaar gharana’ for various reasons. ‘Moradabad was a place with many families of musicians. Ustad amaan ali khan saab’s family was one such family responsible for this name. More than that, it was people who would associate ustad ji with the bhindi bazaar because he lived in Bombay for many years where there were other ustads with a same name. Over a period of time it became very easy to connect and identify to Amaan Ali khan saab of the Bhindi bazaar for all music lovers. He personally would have never said he belonged to Bhindi bazaar gharana. The second most important music family was that of table players Ustad Ahmed Jaan Tirakhwa saab. He belonged to Moradabad, though his style of playing was that of farooqabaad. The third was our family of Sarangi players. My great great grandfather, my grand uncles and many others who patronized this instrument. Many of them left to Pakistan during partition. So the Moradabad gharana has its branches spread far and wide. And now I think it’s time to give this gharana its due and that’s why I have kept it a little aside from Bhindi bazaar and let everyone know the original name’ says Murad clearing the air off this much confused turf.

Moradabad is the foremost of gharanas that patronized Sarangi along with other gharanas like Panipat, delhi, Jhajhar and Kirana. Sarangi, an instrument whose history has been well-documented has several interesting stories. In the days of yore, in the Middle East one hakeem Boo Ali Ibn Sina, a student of the famed Pythagoras is said to have gone into the forests to collect plants and roots for his herbal medicines when he heard strange music emanating from under a tree. On closer scrutiny he noticed that entrails of a dead monkey whose intestines were being rubbed by a dry twig under the breeze were producing this music. In Abul Fazl’s famous Ain-e-akbari this story finds itself with a different discoverer. In the current times, the strings of the sarangi are made out of goat’s intestines. In Rajasthan an earlier version of this instrument called Ravanhattho and Kamayacha with three main strings and about 15 sympathetic strings was in usage for a long time. The Kingri in Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh, the Kunju in kerala, Pen in Manipur and banam and kenara in Orissa were all various earlier rural avatars of the same Sarangi devoid of all ornamentation. From the point of view of its shape and structure the ancient musical instrument without the frets called Ghosvati or Ghoshak veena was perhaps the closest to the latter day Sarangi. In more modern parlance, the Pinaki veena, a gut-string bow instrument described in Saranga deva’s Sangeet Ratnakara (13th century A.D) bears a close resemblance to the sarangi we know. The modern day sarangi is a far accomplished and highly engineered instrument. ‘Sarangi Sau rangi’ , (the sarangi has a hundred colour) is an adage that goes aptly well with this instrument’s virtuosity to create such delicate and fine music. Played with cuticles and the lowest part of the finger nails, it is not an easy instrument to master. What started off as an accompanying instrument has slowly taken shape of being a classy solo concert instrument, thanks to the undying efforts of Ustads from all these gharanas.

Speaking of his early days of learning music Murad recollects his taleem under his gurus. ‘I would have to spend many studious hours in riyaaz. It was not easy to see my cuticles bleed and feel the pain. I would just stick bits of tape around my fingers and carry on with my music practice’. Years of such hard work was bound to pay well and Murad won the first prize at the all India radio national music competition at the tender age of sixteen in 1992. Ever since then, there has been no looking back for him. Having accompanied the likes of Smt Girija Devi, Ustad Rashid Khan, Pandit Gopal Mishra, Pandit Briju Maharaj and many more senior artists from the world of Hindustani classical music and dance, he is currently an ‘A’ grade artist from AIR Delhi.

Murad who feels that vocal music is important, like his seniors first learnt vocal before he graduated to taking the Sarangi. ‘Vocal music is very important especially for sarangi players. When you learn the intricacies of Khyaal and other genres like dadra, tappa, thumri and so on in vocal, it becomes far more easier to practice it on the instrument’ says Murad. His grandfather the great Ustad Saddique Ahmed Khan saab was also a student of Hindustani vocal for twenty years before his gurus allowed him to touch the sarangi. A strong grounding in vocal becomes an essential part of an instrumentalist’s journey into musicdom. There have been many sarangi players who have mastered this instrument. But there have been a very few who can be credited with making sarangi the solo instrument. ‘Ustad bundu khan saab’s name stands out first. He was responsible for changing the presentation and the music of sarangi and taking it to a new stature. After him come Pandit Gopal mishra ji and Pandit Ram narayan ji who was responsible for making it popular in the music festivals across the world. There have been many others too, but you need to see who got the opportunity and who got the right platform to present their skill’, says Murad.

he Sarangi has also been one of the main instruments to provide music for Kathak as a dance form to grow. ‘Initially when I set out to become a solo concert performer, my father also encouraged me to experiment. I was to learn how to play the lehraas with tabla or pakhajwaj as an accompaniment or how to play it with dance. For that I worked in Bharitiya kala Kendra in delhi for about six months to learn this art. The people there wanted me to stay back when I was leaving six months later, but this stay extended for six years and I had to beg myself out of that place to continue my work. But what I learnt there was priceless. The Sarangi is one of the most versatile instruments and can be played with all genres of music and dance forms if it is mastered the right way’, adds Murad.

The Sarangi has come a long way. With the passing over of Hindustani musical patronage from royal courts to emergence of havelis and kothas of the nawabs, the Sarangi started to become associated with mehfils and tawaifs or nautch girls. A little known fact is that even famous senior Hindustani vocalists like Ustad Abdul Karim Khan saab, Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan saab and Ustad Amir Khan saab who had begun their artistic careers as Sarangi players disowned their instrumental past on their path to fame. From classical concerts the Sarangi came to be a more popular instrument among lighter semi-classical forms like Ghazal and soon was adopted by the film industry for playback music. But how many ever such confrontations later, the Sarangi continues to survive the onslaught of time, space, technology and more to constantly keep re-emerging as an instrument worth all ages and all times.

Whatever be the origins of this instrument, many people have come forward claiming to be its original inventors in the past. ‘Earlier sarangi had 4 strings of Sa, Pa, Sa and Pa. In this last century, it was reduced to three strings. Now if I put the forth string back and say it is my invention, it is not right’, says Murad demystifying all these false claims of older artists who were supposed inventors. Being close to human voice and able to replicate patterns of vocal music, the Sarangi is an ideal accompaniment to Hindustani Classical music. The subtleties that can be acquired through sarangi cannot be attained through harmonium due to its limitations. But lately, just for convenience sake, sarangi is being replaced by harmonium. One of the other reasons why its popularity is on the decline is also because of the fact that it is a difficult instrument to learn and master. But Murad with his determined efforts has been credited to elevate the status of the instrument with his fusion concert tours and other musical alliances. ‘I have toured with music groups like Indian Ocean and Shubha Mudgal Ji’s group and we have seen how widely sarangi has been appreciated. I have collaborated with pianist Anil Srinivasan from Chennai and done classical fusion. I love innovation and love experimenting because this instrument easily accommodates such practices. Its musical limitations are almost negligible and hence for a player like me it comes as a blessing’ says Murad speaking about his musical collaboration.

There is a falsehood generated by popular perception that Islam is against music and those Muslims who practice music are anti-Islamic. Breaking that myth once the late Bharat Ratna Ustad Bismillah Khan saab had said that those who say music is anti-Islamic know nothing of music or of Islam. ‘This is not true. Music is very much a part of all cultures. I have been to Jerusalem to the tomb of one of our saints and I was surprised to find the design of a violin engraved on his mazaar in that dargah. There were music notes written on the chaadar along with figures of other musical instruments because the saint himself must have been a person of music. So there is no such thing in Islam. That kind of culture which encourages excessive alcoholism, domestic abuse and violence and other immoral activities must not be encouraged anyways be it Islamic or not. It’s harmful for the society anywhere in the world. In fact Islam says a lot more things are haraam, why target something as divine as classical music? Classical music is pure and nothing can touch it’, says Murad with affirmation against all these rumours that do more harm to music and to Islam than anything else.

Having over a dozen albums of solo and non-solo music albums to his credit, Murad is the new face of Sarangi amongst the performance and festival circles. The ‘Saurangi’ festival conceived and created by him and his team of efficient musicians was a landmark festival in the history of Sarangi as well. It is an annual feature marked on the musical calendar where a sarangi symphony is performed by a dozen players who play a scripted symphony. For the first time ever in the history of Hindustani classical music, the best of hundreds of Sarangi players and music connoisseurs gathered under one umbrella to enjoy a festival dedicated to this instrument. ‘In the past Pandit Ram Narayan did a similar event with hundred sarangis but that event was on a different level. I have tried to put together an Indian symphony like how Pandit Ravishankar used to do the national orchestra with different instruments’, says Murad about the Saurangi festival. Murad along with his twin brother Fateh ali , sitar player , vocalist imran khan and tabla player Amaan Ali have formed a group called ‘Taseer’. Taseer as a band has collaborated with many more musicians from across the world according to the needs of performances.

Ask him if he believes if it’s possible to become a full time professional musician and he says ‘Yes! Why not! It depends on how much riyaaz you do, how committed you are to your music. Nothing is impossible’, he says.

With such exponents like Murad Ali in its fold, the Sarangi can be proud to make a fresh come-back on the concert stage more actively. Murad proved many a critic who thought that the sarangi was on the verge of extinction, totally wrong with his innovation, bowing techniques and newer musical collaborations. With a well-established aesthetic sense deeply rooted in his great legacy and in the tradition of his Gharana, so far as we have musicians like Murad Ali we can all say that Sarangi and its pristine music are in safe hands.

* * * *

The Bhendi Bazar family of style (gharana)

In North Indian Classical Music, several Systems are prevalent. Unlike many other music systems of the world, which are documented in the written form, Indian music systems are basically tradition bound, and, for past several centuries, have descended only in the oral form from a teacher to a student. A musician practising a certain system of music, is said to belong to that particular musical family, and is locally called to belong to that gharana. Amongst the contemporary ones, Bhendi Bazar is one such gharana of the North Indian Classical Music.

Three singer brothers, Ustad Chhajju Khan, Ustad Nazir Khan, and Ustad Khadim Hussain Khan, who lived in Bijnour town of Moradabad district in the state ot Uttar Pradesh, are the founders of Bhendi Bazar Gharana

Since they hailed from Moradabad district, this Gharana initially was known as Moradabad gharana In early 20th century these brothers migrated to Bombay, and made their home in the southern part of the town called, Bhendhi Bazar. Since the Governor of the state, the elite class, and rich tradesmen also lived in the same locatity, it was full of several activities.

These brothers when started giving their public performances and becoming popular, the listeners lovingly started referring to them as Bhendi Bazarwale Gayak (singers from Bhendi Bazar). Since then, the gharana founded by them has come to be known as Bhendi Bazar Gharana.

It is therefore not surprising that, with such a recent origin, the current performers of this Bhendi Bazar Gharana belong only to its 4th generation.

The gharana lineage shows that it is Ustad Aman Ali Khan who, with his several disciples, was mainly responsible in popularising the Bhendi Bazar Gharana. Sometimes, therefore, the gayaki ( style of singing ) of this gharana is referred to as Aman Ali Gayaki.

Characteristics:

Bhendi Bazar Gharana’s style of singing, in many respects, is clearly distinct and different from several contemporary styles of North Indian Classical Music. The style typifies itself with delicate voice production and bewitching tonal inflections. It stands out with its high – degree rhythmic play, and the tonal arches and swara (note) sequences in it are so balanced and poised that one is reminded of the footwork of a skilled dancer. The bandishas (compositions), mostly composed by Ustad Aman Ali Khan, the doyen of the gharana, under the pen-name Amar, are rich in their literary and poetic content. The singer of Bhendi Bazar Gharana is constantly maintaining a clear and conscious balance between the grammar and aesthetics of music. Rendering of sargam (sequences of musical notes) with intricale laya (rhythmic) patterns and weaving of taanas (note sequences in fast tempo) based on merukhand system, and with high degree of melodic content of pleasing permutations and combinations are some of the other distinctive hall-marks of Bhendi Bazar Gayaki

(Notes by Daniel Schell, from Shaila Piplapure’s biography)

.

. .

. .

.

The most widespread (one of 13) adjustment container: c1, c1; g, g, c1; c; g; g1; g1; c1, c1;. Chromatic tone lines of tar includes 2,5 octaves. The tool range covers sounds from “do” a small octave to “sol” of the second octave, but at play it is possible to take also sounds «la» and «la be mol».

The most widespread (one of 13) adjustment container: c1, c1; g, g, c1; c; g; g1; g1; c1, c1;. Chromatic tone lines of tar includes 2,5 octaves. The tool range covers sounds from “do” a small octave to “sol” of the second octave, but at play it is possible to take also sounds «la» and «la be mol».

You must be logged in to post a comment.