Introduction

Persian santur (san-tour) is a fixed string musical instrument which is played with a couple of light wooden hammers. Santur has an isosceles trapezoidal shape. Its overall shape, tuning design, and playing methods are similar to the American hammered dulcimer and East Indian santoor. Santur’s origin traces back to other instruments “played by striking cords with hammer like implements,” back to ancient Persians in the Middle East, India, and perhaps ancient China. Contemporary santur design, however, is most likely no more than two centuries old. This santur is prevalent mostly in Middle East, but is also used in Greece and Turkey. There are many variations of santur design depending on the region of origin, the musical notes it produces, and preferences of instrument maker and musicians. In fact the santur images in this article vary somewhat from the stated design specifications. In this article, we focus on a santur design that is most popular in contemporary Iran or Persia. Persian pronunciations (e.g. santour) are included (in italics) as a courtesy to the culture that has fostered the evolution of this instrument over centuries. A glossary at the end provides the words in Persian script.

Santur provides over three octaves of musical notes (E3 – F6 or mi3-fa6). Each musical note is delivered by a course of four strings (seem) tuned exactly to the same pitch. The strings of same course share the same chessman style bridge (kharak). In this design, there are two columns of nine courses each, with bass courses on the right, and treble courses on the left. Accordingly, this type of santur is named Nine-bridge (noh-kharak). Treble bridges are positioned so that the resulting two (left and right) treble courses provide two consecutive musical octaves (higher and mid-range) with one additional overlap note. Bridges are positioned on the soundboard. Santur soundboard rests on the frame (kalaaf) which consists of top rail, bottom rail, and hitch pin block on the left and tuning pin block on the right side. Santur frame is attached to the back board opposite to the soundboard. The space encased by the frame rails, soundboard and back comprise the santur soundbox. Every string originates via a loop from a hitch pin (seem geer) over the left side bridge (sheytaanak / zehvaareh) and saddle rod (maftool), sharing a bridge with three other strings in the course. The string then travels to the right side saddle and side bridge and is eventually wound around its own tuning pin (gooshi). There are 72 strings, hitch pins and tuning pins in a “Nine-bridge” santur. Bass bridges are arranged with the top bridge positioned at 50MM, and bottom bridge at 130MM from the right saddle The musical notes on the right side of bass bridges are not used.

The nine phosphorous bronze alloy (bass) string courses provide (E3 – F4 or mi3-fa4). The middle and higher octaves are played on the steel (treble) courses in the middle and left side which are tuned to (E4 – F5 or mi4-fa5) and (E5 – F6 or mi5-fa6) respectively. The two most popular Nine-bridge santur types are distinguished by the tuning of the third (from the bottom) bass course. The most prevalent version has this course tuned to (G3 or sol3), and is traditionally known as G-tuned (sol kouk) santur. The other less popular version is tuned to (A3 or La3) as third bass note, and is traditionally known as A-tuned (La kouk) santur. The latter type provides (F3 – G6 or fa3-sol6) musical note range. This article will focus only on the “Nine-bridge” G-tuned (sol kouk) santur.

About Persian Music

Santur is mainly used in playing traditional (sonnati) music of Persia. It is not conducive to playing Western style music. Persian and generally Middle Eastern music has much more complex nuances than could be discussed here. Most common practice in Persian traditional music is to use the chromatic scale. Tones similar to Quarter-tones (half semitone) notes are also used routinely. A quarter-tone is equal to 50 cents or 2 Pythagorean commas. The scale of Persian music is not fixed on the same twelve notes. Accidental notes are used routinely. Because of these complexities which add additional burden of re-tuning, violin, Persian oud, and other non-fretted instruments are much easier to tune for Middle Eastern music. Quarter-tone note tuning of santur is often accomplished by moving the bridges and not using the tuning pins. This practice, although convenient for the musician, diminishes somewhat the acoustic response of the santur if not its structural integrity.

Persian traditional music differs from its contemporary rhythmic counterpart in that it is melodic, mostly slow and very structured. Singing in the traditional Persian music, to the ears of Westerners, is an enchanting blend of yodeling and Western opera. Traditional Persians are passionate about poetry. The traditional music lyrics though lacking opera like story line, is poetry-based and somewhat similar in lyric tone to that of American blues music.

General Santur Structure

A typical santur structure is said to be under a tensile force equivalent to 900 + Kg (1,980 lb or one ton). It is generally made to be light and portable typically (3–4 Kg or 8 lb), and constructed of thinnest-size parts. From a structural viewpoint, it is relatively no less complex than a wide underground tunnel designed and built by civil engineers. Santur design has an additional requirement in that it must produce pleasant and uniform volume musical sounds.

Frame

The santur frame (top rail, bottom rail, tuning pin block, hitch pin block) resides between the soundboard and the back, and provide the bulk of support for santur’s structure. The frame also plays a role in the tonal quality of the santur. Top side of frame where it is in contact with soundboard is tapered down on the interior edge to minimize the contact area between the soundboard and frame rails.

Top and Bottom Rail

Top and bottom rail provide the main structural support to the pin blocks and somewhat contribute to the acoustic performance of the soundbox. Bottom rail has a sound hole at its center. This design differs from typical Persian santur in that the pin blocks are lapped over the ends of top and bottom rails. Top and bottom rails are thus not extended all the way to the corners or dado joined as practiced in Persia. The lapped-over joint is said to provide better support for the pin blocks.

Tuning and Hitch Pin Blocks

Some Persian santur makers glue three layers of hardwood with the middle later in a transverse grain orientation to prevent cracking of the tuning pin block.

Tuning Pins

Hammered dulcimer tuning pins will work just as well. Refer to the supplier’s specifications for pin sizes.

Shape: overall cylindrical, tapered thread at one end; square or rectangular cross-section at other end – pierced to accommodate string winding

Material: Nickel or chrome plated steel Overall length: 41MM

Tapered thread length: 23MM

Diameter: 5MM

Square end side: 4MM

Hitch Pins

Hammered dulcimer hitch pins will work just as well. Refer to the supplier’s specifications for pin and drill bit sizes.

Shape: cylindrical Material: Nickel or chrome plated steel

Length: 25.5MM

Diameter: 3.7MM

Pin Holes

There is one hole for each string in the tuning and hitch pin blocks. The holes are arranged in a single column, although some suggest staggering of the holes as well. There are eighteen columns and four holes per column. Drilling these 144 holes in the pin blocks is a tedious process, and requires accuracy as well as patience. Using jigs and prior practice is definitely recommended.

Soundboard

Soundboard covers the upper part of frame rails. Be sure to drill / carve the sound holes at proper location on the soundboard before gluing. Soundboard is the most costly piece in santur in terms of the wood, cut and quality. Use a separate 10MM thick piece of scrap wood on top of the soundboard when and if drilling to prevent splintering. Practice drilling on scrap wood first. A good soundboard is made of dense and dry wood like walnut. It has uniform fine wood grain lines (2–3MM apart) in parallel with the strings with little or no anomaly in the wood pattern. Thinner soundboards provide best tonal quality in a santur. The vertical stress on the soundboard comes from the bridges (downward) and from the frame rail and soundposts (upward). The areas on a soundboard most vulnerable to cracking are the strips at the top and bottom edges of the soundboard, between the frame rails and the nearest bridge. Some santur makers vary the thickness (up to three different sizes) of the different regions of soundboard to accommodate this. You will find it easier if you measure the exterior dimensions of soundboard and back slightly larger (1–2MM) and trim it by sanding or routing after the construction is completed. Mark the precise location of sound holes on the soundboard.

Back

Back board encases the lower part of frame rails completing the soundbox and supporting the soundboard via soundposts. It will help a lot to draw the diagram of santur on the back board and identify precise location of soundposts, frame rails, etc. You will find it easier if you measure the back panel slightly larger (1–2MM) and trim it after the construction is completed. Mark the precise location of frame and soundposts on the inside of the back board.

Soundposts

Santur has four support soundposts and one tuning soundpost inside the soundbox between the soundboard and the back. Support soundposts are glued to the back board only. Soundposts are not glued to the soundboard. Soundposts must not be positioned closer than 19MM to any bridge; must be installed in horizontal positions between adjacent bridges; and not in a column parallel with any bridge column. The santur design presented here, strives to accommodate occasional tuning-movement of bridges by adding additional clearance between the soundposts and the nominal bridges. General location of these soundposts is as follows;

• Between and to the left of C & D bass bridges

• Between and to the left of B & C treble bridges

• Between and to the right of C & D treble bridges

• Between and to the left of F & G treble bridges

There is also one “tuning” soundpost which is intended to balance or regulate the tonal balance of santur’s music box. The latter is installed only after the santur is completely assembled and a string is tuned. Tuning soundposts are not glued at all.

Bridges

Bridges are customarily turned from hardwood; one bridge for each course in contemporary santurs. Taller bridge heights are used with harder wood like walnut. Taller bridges also increase the stress on the soundboard. Individual bridges in santur facilitate semi/quarter tone adjustment of string notes by moving its bridge instead of using tuning pins. This practice is counter to maintaining the structural integrity and tonal quality of a santur, and may shorten the useful life of a santur. Bridge bottom (khazineh) surfaces are carved (actually turned) in a concave manner with a rim of about 1–2MM wide, and depth of 1–1.2MM. Bass bridges are located with string length of 50MM and 130MM from the right saddle (top and bottom respectively – center to center). Treble bridges are located at approximately 1/3 distance (center to center) from the left saddle so that the left side of each course produces the pitch of the same note in the next higher octave. Bottom surface of bridges should be sanded and polished to a smooth surface. Bridge cap (saachmeh) should be made of tempered nickel plated steel rods. Do not use Delrin rods or bronze rods for santur.

Bridge caps:

Shape: cylindrical

Material: Nickel or chrome plated steel

Length: 16MM

Diameter: 2.5MM

Side Bridges

Make side bridges from hardwood like walnut. Tuning side bridge is installed with 2MM over-hang along the pin block. Saddles or side bridge caps should be made of tempered nickel plated steel rods with same material and diameter as hitch pins. Do not use Delrin rods or bronze rods for santur.

Wood

Selection – More dense varieties of walnut and birch are the primary wood used for making fine santurs in Persia. Other hardwood such as Siberian Elm (Choob-eAazaad), betel palm (foofel), and mulberry wood have also been used. Autumn lumbered, fine fiber dense wood from warm and dry climates is more suitable for making santur. The narrower and closely aligned grain lines, the more suitable the wood. Forest grown trees tend to grow more straight and thus produce more uniform wood than the urban variety. Climate change and other factors influence the closeness and width of the rings in cross section of trees which produce the grain lines. There should be no knots or other anomalies in the wood grain of the soundboard. Use of soft or unseasoned wood should be avoided. There is no requirement that you use different types of wood in santur. The same type of wood can pretty much be used for all the pieces.

Seasoning – The wood for musical instruments must be prepared dry and free of tree sap and oil. Steaming is sometimes used to dissolve and extract the tree sap within the wood fibers for thinner pieces. Heating of the wood in a large kiln or pizza oven is another method to “boil the sap” out of the wood. This process requires experience and care must be taken so that the wood remains hard yet flexible. Fully seasoned wood should have between 12-15% (never over 19%) moisture and this could take a long time if it is done naturally. The wood that is dried naturally in the shade and in the flow of air for an average of a couple of years produces the best sound quality. Wood that has not been seasoned adequately is susceptible to warping and produces inferior tonal performance. To maintain a good sound quality, keep the santur away from exposure to moisture and sunlight. Store this instrument in its own case with desiccating chemicals or drying agents.

Strings (seem)

Use only the type of steel string made for musical instruments (music or piano wires). Strings are susceptible to rusting in humid environment. Chrome or nickel plated music steel wire is used for treble strings and phosphorus bronze plated steel music wire is used for bass strings. Gauges are .015″–.016″ (.38MM–.41MM). All strings are looped at hitch end, and wound at tuning end, with minimum of (7) windings to ensure stable winding.

Hammers (mezrab)

Santur is played with a couple of wooden hammers (mezrab), much thinner, lighter (4 grams) and traditionally more ornate than those of American hammered dulcimers. The short dimensions of santur hammers (22–24MM x 30MM) make it possible to use just about any types of dry light, very dense but high resonance hard wood like rosewood. The striking surface tips of hammers are sometimes covered with felt to produce a milder sound.

Glue

Use an adhesive that provides a good bond and cures to at least the same hardness as the soundboard. Persian santur makers use a gelatin based hot hide glue (serishom), which when heated indirectly and applied, dries to a hard, durable and moisture free texture. Steam is used in a double layer pot to heat this glue. You can use any type of glue which is appropriate for American hammered dulcimer including Franklin’s Tightbond II.

Wood Finish

Santur finish must dry fast without much penetration in the wood; protect exterior of santur surface against heat and moisture; endure high pressure from bridges and transmit vibrations from the bridges to the soundboard without flaking or cracking. Persian santurs are coated with a natural spirit varnish after the trimming, sanding and sometimes staining. The varnish is a mixture of lacquer as main resin and alcohol (lock-alkol). Somewhat darker non-reflecting finishes are preferred for santur. Color pigments stains are also used to improve color tone of lacquer. Violin shops are good places to get advice about varnish for santurs.

Construction Steps

Santur building is a time consuming project. Measurements must be made with less than one Millimeter tolerance. Having a viable blueprint and instructions is a must. If you are not experienced with woodworking, or have not previously built musical instruments, practices building each piece with scraps of wood until you are satisfied with the results. It is helpful to construct each piece as specified before attempting assembly. It also helps to build a frame jig from scrap wood that would surround and hold the frame of your finished santur frame while the adhesive cures. Always have the retaining clamps ready to use. Dry run the gluing process before you actually apply the glue to make sure everything is ready once the glue is applied. Practice gluing and curing on scrap wood to gain expertise in glue application. Always wipe any extra glue immediately after the clamps are applied. Take care to not let the adhesive get on the surrounding jig or retaining clamps. After the curing of the glue is complete, sand the inside of any visible glue. Sand and dust the inside surfaces to a smooth finish. Inside of your santur soundbox should be somewhat smooth and free of any visible glue marks. Do not use nails.

1. Prepare the Pieces – Cut and prepare each piece in precise dimensions according to the blueprint. You will find it easier if you measure the soundboard and back panel slightly larger (1–2MM) and trim afterward. Draw the layout on the interior surface of back board and identify the position of the support soundposts on the drawing. Draw the layout on the exterior surface of soundboard and identify the position of the sound holes on the drawing.

Pre-drill all holes in pin blocks. This is probably the most difficult part of building a santur as these holes are all at angle to the pin block surface (parallel to the courses). It is helpful to use a template or more preferably a jig to obtain precise cuts and holes. For best holes, keep your drill bits sharp and cool. A wood hole with charred inside will not be able to hold the string tension. When drilling, use separate10MM thick pieces of wood scrap between the drill and the santur surface to minimize splintering. Use a stopper guide or bushing around your drill bit to prevent drilling through the pin blocks. American dulcimer makers have found that counter sinking the holes by 1–2MM improves the aesthetics of their instruments. If you mis-drill a hole, the whole pin block will most likely need to be replaced. Blow out any dust that may have collected inside the pin block holes.

2. Glue Soundposts to Back – The back and soundposts can be cut and assembled at this point. Use a level or lay the back on top of the soundposts to verify uniform height of soundposts. A thread spool- like block may be used to ensure the correct vertical orientation of the soundpost on the back while the glue is curing. Take care to insure vertical orientation and uniform height between soundposts.

Remove any dust from interior of the pieces. Dry fit the frame pieces together on a flat surface to ensure tight fit, uniform height, and adequate surface contact. Test use of jigs and / or clamps to hold the glued pieces together while curing. Glue the frame pieces two pieces at a time (top rail and hitch block, and bottom rail and tuning pin block), and then complete the gluing of the final two pieces.

There are two approaches in the way you order gluing the back and soundboard to frame. The first approach (practiced in Persia) glues the frame to the back first, then the soundboard. The second approach (described here) would glue the soundboard to the frame first then the back. The advantage of the second approach is that if there are any problems with the height of the soundposts or if you feel you must correct for any warping in either boards, you still have one more opportunity to adjust the height of, or even replace a soundpost. A second advantage of the latter method is that gluing of the soundboard to the frame is more of a delicate process because the surface being glued is tapered. Gluing and having access to the interior side of the glued surface enables you to better clean any glue overlap. You do not have that option with the first approach unless you remove the back first.

3. Glue the Soundboard to Frame, then Frame to the Back – Spread the glue only on the narrow flat edge near to the exterior edge at the top of frame where the soundboard would be attached. It is important that you use the glue sparingly, and avoid gluing the tapered part of the top of the frame. Place and glue the soundboard on top of the frame using sturdy clamps.

Verify that the height of soundposts is 1–1.5MM above the frame by placing the back on top of the frame. The back should sit on soundposts with a 1MM gap with the frame. This is a critical step. If a soundpost is too short, the benefit of soundposts is essentially nullified and buzzing may even render your instrument useless. If a soundpost is too tall, it will create problem for other soundposts. Correct any problem before proceeding to the next step.

Next glue the frame to the back being careful not to tip over any of the support posts. Do not glue the top of supporting posts. You will need to use a dozen sturdy clamps to press the frame against the back in spite of the resistance by the soundposts. Do not remove the clamps until the glue is fully cured. This may take several days. Once the glue is cured, any over-hanging part of the soundboard and back may be removed by sanding or routing. After the bond between the back and frame rails is cured, the side bridges may be glued and clamped on to the soundboard.

4. Mark and carve the string guide notches on the exterior side bridges -Santur strings tend to ride up toward the top side if not guided properly. The grooves or notches on the outer edge of side bridges play an important role in the spacing between and alignment of strings on the bridges. If these notches are not laid properly, the player will see uneven spacing of strings on a course and between courses which is least desirable. It may help to use wooden dowels in tuning pin holes so that proper contact point of the strings with tuning pins may be best approximated. Place saddles on both bridges. Mark the top outer edge of the side bridge where the center positions of the 18 courses will be located. The center position is half way between the second and third string in a course. Mark the notch locations 2MM apart measured along the bridge length around the center positions. Bend a solid 2MM thick wire in form of letter “J” with a length of 100MM and bottom diameter equal to the diameter of a tuning pin. You will be using this J-rod to approximate the path of the string for which you are creating the notch. Mark the side bridges as close to, and parallel to the J-rod direction. Continue this process for the bottom and top strings of every course, and then mark the position of other strings evenly. Use a very thin (0.3MM) finishing X-acto razor saw to carve the notches starting at the top of the bridge and ending about 1MM below the top surface of the pin block. The groove depth should be curved to best approximate the natural path of the strings from saddle to the tuning pin. Place the string inside the first few grooves to test the correct angle and width of the cut. If you cut too shallow, the pressure from the strings may crack the side bridge or work against the adhesion of the bridge to the soundboard. If you cut too deep it may undermine the ability of the side bridge to keep the strings in tune. You may want to practice on a scrap wood first. Repeat this process for the hitch pin block.

It is customary to test the sound quality of the santur at this point. An experienced ear is an absolute requirement. First tap the instrument with finger tip and listen to the echo sounds form the music box. Next install a single string for the treble “B” or “C” course including the bridge in the correct location and examine the sound. The string and hardware is removed following this test.

5. Apply stain and finish – Give your santur its last sanding and clean it dust-free with a tack cloth. If you plan to stain your santur, be sure to use an alcohol (not water) base stain. Moisture is the #1 enemy of the tonal quality of santur. Use a small rag, soaked dry in stain to lightly rub the surface of santur. Darker colors and mat finishes are preferred because they minimize reflection of light from playing surface and make it easier for the musician to see the string courses. If the colors are too dark, they show off dust and absorb more heat from sunlight. You may need to repeat this step to darken the stain, but avoid pressing the rag against the surface as doing this will enable the moisture to get inside the wood. Be mindful of getting any stain or finish inside the pin block holes. Pat dry (or floss) corners, edges and groove areas where the stain tends to over-darken the surface. Place the santur in a moisture free warm location and let the stain dry completely (up to several days) before applying the varnish. The best varnish product for a santur is one that dries to a durable finish; the harder the better. Let the finish dry for a few days. Persian santur makers use a mixture of natural colors by boiling skin of walnuts, pomegranate, copper sulfate and tree sap. As a varnish, a 1:3 mixture of lacquer or shellac flakes and methyl alcohol (lock-alkol) is also used.

6. Install hitch and tuning pins – Gently tap in the hitch pins so that all but 5–7MM of it remains outside of the hitch pin block. A uniform protrusion of these pins enhances the appearance of your santur. Practicing the next few steps on scrap wood is recommended. It is helpful during tuning to use blue plated tuning pins for treble strings and nickel plated pins for bass strings. Measure the depth of a tuning pin hole and mark the tuning pins so that your tuning pin will not penetrate the holes beyond their depth. Doing so will crack your tuning pin block. Gently tap the first 1–2MM of the tuning pins into the holes until you get a straight and firm footing and then screw in the next few MM until you feel the tight grip of the wood. You will be turning the tuning pin clockwise. Do not use power tools for this step and do not press the tuning pin in while turning it. A wooden dowel with markings can insure uniform penetration between pins. You may want to test the adequacy of penetration of tuning pin on the upper treble strings first.

7. Install the bridges and strings – The upper strings of courses are installed first. The remaining strings are installed from bottom up alternating between the treble and bass courses. Loop the strings by clamping the ends of a loop (50MM long) adjacent to each other in vise, and turning the loop with a steel rod exactly 7 revolutions. Other method will suffice. Install the string by hooking the loop around the hitch pin inside the corresponding side bridge grooves and over the side bridges saddles. Keep the string taught while threading. Take care to unwind the string from its spool while doing so. Thread the string through the corresponding tuning pin eye and cut the string with about 60–70MM slack beyond the tuning pin. Bend the last 5MM tip of the string to make it easier for the string to stay in the tuning pin eye. You will be turning the tuning pin clockwise with the saddle side of the string rapped on the inside. It is helpful to guide the string with your fingertip. Keep an eye on the alignment of the string with the side bridge grooves. When the tension on the sting is tight enough to hold the string, continue to install the other strings in the course. Install the bridge for the courses. Wear eye-protective gear while doing this. Snip any excess string from the tuning pin.

8. Tuning the Santur – Tuning the strings is done by using a Tuning Wrench (kelid) that matches the end shape of tuning pins. Santur strings are ordinarily tuned to the key of G from bottom to top (E F G A B C D E F) with the middle (C – do) bass note being equivalent to the middle C 4 in piano. Check the alignment of bridges before you start tuning the strings. Tune the top and bottom treble strings and double check the harmonic pitch of the left and right treble strings. Tune the santur one octave lower first time and let it rest for a few days to allow the wood to adjust to the string tensions. Tune the top string of a course for all courses, and then continue with the second string and so on until the first tuning phase is completed. After the first tuning phase is complete, check the sides of the santur for signs of warping.

The tuning of the soundbox is made by installation of the tuning soundpost. The purpose of this soundpost is to regulate the echo characteristics of the soundboard so that a pleasant and uniform volume is produced by all santur courses. This step is rather tricky in that that it is used to adjust the lack of balance of sounds across courses. Furthermore, access to the inside of the soundbox is limited to the treble sound hole and the hole at the center of the bottom rail. The method used in Persia is as follows. The soundpost is held by two long nose metal pieces (like chopsticks) which are bent in the middle for better handling. A fabric string holds the soundpost firmly between the chopsticks. The string is knotted in such a way that by pulling its end, the soundpost is disengaged from the chopsticks thus allowing you to retrieve them from inside of santur. As of late a new tools have been devised to accomplish this. You may need to improvise your own installation tool.

Final tuning of santur may be accomplished at this point. Never tune the santur to higher octaves as doing this will structurally damage the instrument.

Playing the Santur

As with all musical instruments, good playing techniques from the onset help the musician avoid poor habits. To play the santur, the player stands, or sits on the floor with legs crossed, facing the santur at the bottom end. The payer’s forearms are held parallel and approximately 100–150MM above the soundboard. Santur hammers are held between the index and middle fingers, and are moved by the wrests, and not by the forearms.

Courses are struck 30–40MM from the bridges. Acquiring these playing skills is said to take a long time.

Santur Case

Santur case is made of a hard shell, and is padded on the inside to protect santur against shock and moisture. Santur strings should be loosened when freighting or transporting santur in rough train to protect the soundboard from cracking. Drying agent (Silicone based) packets are recommended to be used inside the santur case in humid climates.

Location of Sound Holes and Soundposts (MM)

Vertical distance to bottom edge

Horizontal distance to bottom corner

Bass Sound Hole (Horizontal distance measured from RIGHT frame corner) 142 330

Treble Sound Hole (Horizontal distance measured from LEFT frame corner) 107 227

Soundpost #1 (Horizontal distance measured from RIGHT frame corner) 163 299

Soundpost #2 (Horizontal distance measured from LEFT frame corner) 152 298

Soundpost #3 (Horizontal distance measured from LEFT frame corner) 174 405

Soundpost #4 (Horizontal distance measured from LEFT frame corner) 84 378

Acknowledgement

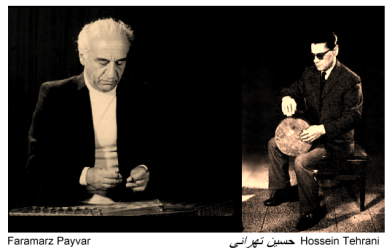

The contemporary santur in Iran owes a great deal to the dedicated lifetime work of santur makers such as (Mehdi Naazemi). These master instrument builders contributed to Persian music by leaving a legacy of not only beautifully sounding santurs but more importantly by sharing their decades of knowledge and experience with others.

The goal of this article is to document a design for santur in form of an introduction including the text, diagrams, design parameters and other specifications. The target audience is the Guild of American Lutherie readers and English speaking instrument builders who generally have access to woodworking information and supplies. Although every effort was made to keep this design reasonably close to the overall contemporary santur specifications, it is not represented as an authentic, acceptable-by-all authority on this instrument. The author’s hope is that this article will begin a dialog on this instrument amongst the instrument experts, builders, and musicians through whose participation, will emerge a future standard and guide for design and construction of contemporary Persian santurs. The author is indebted to Tim Olsen for his graphic support, editing and most of all coaching and patience, and to Nasser Shirazi for courteous encouragement and valuable information sources he unselfishly offered to this project.

Sources

There is an immense amount of information about material and construction tips for hammered dulcimer and other musical instruments in GAL archives, books and Internet that would be very helpful to santur builders.

“Building the Kamancheh” by Nasser Shirazi

American Lutherie #4, BRBAL 1

“Building the Tar” by Nasser Shirazi

American Lutherie #10, BRBAL 1

“A Practical Approach to Hammered Dulcimers” by John Calkin

American Lutherie #41, BRBAL 4

Understanding Wood by R. Bruce Hoadley

Identifying Wood by R. Bruce Hoadley

Taunton Press

Self-Learning of Santur by Hossein Saba

Iran – 1959 – Farsi language

Santour va Naazemi by Arfa’ Atra’i

Part Publishing – Iran – Farsi language

Vijhegi-e Santour by Mehdi Setaayeshgar

Iran – Farsi language

Setar Construction by Nasser Shirazi

Glossary

English Translation Farsi Pronunciation Farsi

A-tuned la kouk لاکوک

betel palm foofel فوفل

bridge bottom khazineh خزینه

bridge cap saachmeh ساچمه

bridge kharak خرک

frame kalaaf کلاف

G-tuned sol kouk سل کوک

hammers mezrab مضراب

hitch pin seem geer سیم گیر

hot hide glue serishom سریشم

nine-bridge noh-kharak نه خرک

saddle rod maftool مفطول

santur santour سنتور

shellac lock lock-alkol لاک الکل

Siberian elm Choob-e Aazaad چوب آزاد

side bridge sheytaanak / zehvaareh شیطانک \ زهواره

sound holes gol-e santur گل سنتور

strings seem سیم

traditional music of Persia sonnati سنتی

system of traditional Persion music radeef ردیف

building blocks of radeef dastgah دستگاه

tuning pin gooshi گوشی

tuning wrench kelid کلید

(Courtesy by Javad Naini)

You must be logged in to post a comment.