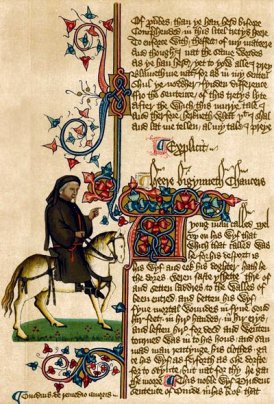

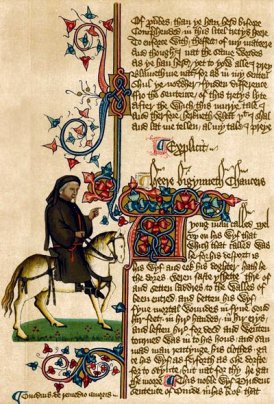

The Parliament of Fowls

by

Geoffrey Chaucer

The life so short, the craft so long to learn,

The assay so hard, so sharp the conquering,

The fearful joy that slips away in turn,

All this mean I by Love, that my feeling

Astonishes with its wondrous working

So fiercely that when I on love do think

I know not well whether I float or sink.

For although I know not Love indeed

Nor know how he pays his folk their hire,

Yet full oft it happens in books I read

Of his miracles and his cruel ire.

There I read he will be lord and sire;

I dare only say, his strokes being sore,

‘God save such a lord!’ I’ll say no more.

By habit, both for pleasure and for lore,

In books I often read, as I have told.

But why do I speak thus? A time before,

Not long ago, I happened to behold

A certain book written in letters old;

And thereupon, a certain thing to learn,

The long day did its pages swiftly turn.

For out of old fields, as men say,

Comes all this new corn from year to year;

And out of old books, in good faith,

Comes all this new science that men hear.

But now to the purpose of this matter –

To read on did grant me such delight,

That the day seemed brief till it was night.

This book of which I make mention, lo,

Entitled was, as I shall quickly tell,

‘Cicero, on the dream of Scipio’;

Seven Chapters it had on heaven and hell

And earth and the souls that therein dwell:

As briefly as I can treat of its art,

I’ll tell you, of its meaning, the main part.

First it tells how when Scipio came

To Africa, he met Massinissa,

Who in his arms embraced the same.

Then it tells of their speeches, all the bliss there

That lay between them till the shadows gather,

And how at night his grandfather, so dear,

Scipio the Elder, did appear.

Then it tells how, from a starry place,

His grandfather had him Carthage shown,

And told him in advance of all his grace

And taught him how a man, learned or rude,

Who loves the common good and virtue too

Shall unto a blissful place yet wend,

There where joy is that lasts without an end.

Then he asked if folk that have died here

Have life and dwelling in another place;

And his grandfather said, ‘Have no fear,’

And that our present world’s brief space

Is but a kind of death, whose path we trace,

And virtuous folk after they die shall go

To heaven; and the galaxy did him show.

Then showed him how small our Earth appears

Compared to the heavens’ quantity;

And then he showed him the nine spheres,

And after that the melody heard he

That comes from those spheres thrice three,

The source of music and of melody

In this world here, and cause of harmony.

Then he told him, since Earth is so slight,

And full of torment and so little grace,

That he should never in this world delight.

And then he said, that in a certain space

Of time, return the stars would to their place

Where they had been at first, and out of mind

Pass all things in this world done by mankind.

Then Scipio prayed he would tell him all

The way to come into that heavenly bliss;

And he said: ‘Know yourself first immortal,

Be sure to work busily, wisely in this

World for the common good, you’ll not miss

The path that leads swift to that place dear,

That full of bliss is, and of souls clear.

But breakers of the law, he did explain,

And lecherous folk, after they are dead,

Shall whirl about the Earth ever in pain

Till many an age be past, and then indeed

Forgiven for their every wicked deed,

Then shall they come unto that blissful place,

To come to which may God send you his grace!’

The day began to fail, and the dark night

That relieves all creatures of their business

Bereft me of my book for lack of light,

And to my bed I began me to address

Filled full of thought and anxious heaviness,

For I yet had the thing that I wished not,

And the thing that I wished I had not got.

Yet finally my spirit at the last

Full weary of my labour all the day

Took its rest, sent me to sleep so fast

That in my sleep I dreamed there as I lay

How that Elder in selfsame array

Whom Scipio saw, who long ago had died,

Came and stood there right at my bedside.

The weary hunter sleeping in his bed

To the woods again his mind will go;

The judge he dreams how his pleas are sped;

The carter dreams of drawing carts below;

The rich, of gold; the knight fights with his foe;

The sick person dreams he drinks a tun;

The lover dreams he has his lady won.

I cannot say if it was reading fair

Of Scipio the Elder just before,

That made me dream that he stood there;

But thus said he: ‘Yourself so well you bore

In looking at that ancient book of lore,

Macrobius himself thought not so slight,

That I would something of your pain requite.’ –

Cytherea, you blissful lady sweet

Whose firebrand at your wish robs us of rest

And made me to dream this dream complete,

Be you my help in this, your aid works best;

As surely as I saw you north-northwest,

When I began my dream for to write,

So give me power to rhyme and indite.

Scipio the Elder grasped me anon,

And forth with him unto a gate brought

Encircled with a wall of green stone;

And over the gate, in large letters wrought,

There were verses written, as I thought,

On either side, between them difference,

Of which I shall reveal to you the sense.

‘Through me men go into that blissful place

Of heart’s healing, and deadly wounds’ cure;

Through me men go unto the well of Grace

Where green and lusty May shall ever endure;

This is the way to all fairest adventure;

Be glad, oh Reader, and your sorrow off-cast,

All open am I; pass in, and speed you fast!’

‘Through me men go,’ then spoke the other side,

‘Unto the mortal blow of the spear,

Which Disdain and Haughtiness do guide,

Where tree shall never fruit nor leaves bear.

This stream leads you to the grim trap where

The fish in its prison’s lifted out all dry;

Avoidance is the only remedy nigh!’

In gold and black these verses written were,

Which I in some confusion did behold,

For with the one ever increased my fear,

Yet with the other did my heart grow bold.

The one gave heat to me, the other cold;

Fearing error, no wit had I to choose

To enter or flee, to save myself or lose.

As between adamantine magnets two

Of even strength, a piece of iron set

That has no power to move to or fro –

For though one attracts the other will let

It move – so I, that knew not whether yet

To enter or leave, till that Scipio my guide

Grasped me and thrust me in at the gates wide,

And said, ‘It appears written in your face,

Your error, though you tell it not to me;

But fear you not to come into this place,

Since this writing is never meant for thee,

Nor any unless he Love’s servant be;

For you for love have lost your taste, I guess,

As a sick man has for sweet or bitterness.

But nonetheless, although you are but dull,

What you cannot do, you yet may see;

For many a man that can’t resist a pull

Still likes at the wrestling for to be

And deems whether he does best, or he,

And if you have the cunning to indite,

I’ll show you matter of which you may write.

With that my hand in his he grasped anon,

From which I took comfort, and entered fast;

And, Lord, I was so glad that I had done!

For everywhere that I my eyes did cast

Were trees clad with leaves that always last,

Each of its kind, of colour fresh and green

As emerald, that a joy ‘twas to be seen.

The builder’s oak, and then the sturdy ash;

The elm, for pillars and for coffins meant;

The piper’s box-tree; holly for whip’s lash;

Fir for masts; cypress, death to lament;

The ewe for bows; aspen for arrows sent;

Olive for peace, and too the drunken vine;

Victor’s palm; laurel for those who divine.

A garden saw I full of blossoming boughs

Beside a river, through a green mead led,

Where sweetness evermore bountiful is,

With flowers white, blue, yellow and red,

And with cold well-streams, nothing dead,

Which are full of fish, small and light,

With red fins and scales silver bright.

On every bough I heard the birds sing

Angelic voices in their harmony;

Some their fledglings forth did bring;

And little rabbits to their play went by.

And further all about I did espy

The fearful roe, the buck, the hart, the hind,

Squirrels, and small beasts of noble kind.

Instruments, their strings all in accord

I heard played with ravishing sweetness

That God, who maker is of all and lord,

Never heard better, or so I guess;

Therewith a breeze that could scarce be less,

Made in the leaves green a noise soft

In harmony with the fowls’ song aloft.

The air of that place so temperate was

There was no awkwardness of hot or cold;

There waxed every wholesome herb or grass,

Nor no man there is ever sick or old;

Yet was there joy more a thousand-fold

Than man might tell; nor was it ever night

But ever clear day to every man’s sight.

‘Neath a tree, by a well, saw I displayed

Cupid, our lord, his arrows’ forge and file;

And at his feet his bow all ready lay,

And Will, his daughter, tempered all this while

The arrow-heads in the well, and with hard file

She notched them afterwards so as to serve

Some for to slay; some to wound and swerve.

Then was I aware of Pleasure nigh,

And of Adornment, Lust and Courtesy,

And of Cunning, able and with the might

To force a person to perform a folly –

I will not lie, disfigured all was she –

And by himself under an oak I guess

I saw Delight, standing with Nobleness.

I saw Beauty, lacking all attire,

And Youth, full of games and jollity,

Foolhardiness, Flattery, and Desire,

Message-sending, Bribery, and three

Others – whose names shall not be told by me –

And upon pillars tall of jasper long

I saw a temple of brass, sound and strong.

About the temple dancing every way

Went women enough, of whom some were

Fair in themselves and some dressed full gay;

In gowns, hair dishevelled, danced they there –

That was their duty always, year on year –

And on the temple, of doves white and fair

Saw I sitting many a hundred pair.

Before the temple door full soberly

Dame Peace sat with a curtain in her hand:

And beside her wondrous discreetly,

Dame Patience sitting there I found

With pale face upon a hill of sand;

And next to her, within and without,

Promise and Artfulness, and their rout.

Within the temple, from sighs hot as fire

I heard a rushing sound that there did churn;

Which sighs were engendered by desire,

That made every altar fire to burn

With new flame; and there did I learn

That all the cause of sorrows that they see

Comes from the bitter goddess Jealousy.

The god Priapus saw I, as I went,

Within the shrine, pre-eminent did stand,

Placed as when the ass foiled his intent

By braying at night, his staff in his hand;

Full busily men tried as they had planned

To set upon his head, of sundry hew,

Garlands full of fresh flowers new.

And in a quiet corner did disport

Venus and her doorkeeper Richness,

She was full noble, haughty in her sport;

Dark was the place, but afterwards lightness

I saw, a light that could scarce be less,

And on a bed of gold she lay to rest

Till the hot sun sank into the west.

Her golden hair with a golden thread

Was lightly tied, loose-haired as she lay,

And naked from her breast to her head

Men could view her; and truly I must say

The rest was well covered in its way

Just with a subtle veil from Valence;

No thicker cloth served for her defence.

The place gave out a thousand savours sweet,

And Bacchus, god of wine, sat there beside,

And Ceres next who does our hunger sate;

And as I said, the Cyprian there did lie,

To whom, on their knees, two young folk cried,

For her help; but there I passed her by,

And further into the temple I did spy

That, all in spite of Diana the chaste,

Full many a broken bow hung on the wall

Of maidens such as their time did waste

In her service; and pictured over all

Full many a story, of which I shall recall

A few, as of Callisto and Atalanta

And many a maiden whose names I lack here;

Semiramis, Candace and Hercules,

Biblis, Dido, Thisbe and Pyramus,

Tristram, Iseult, Paris and Achilles,

Helen, Cleopatra and Troilus,

Scylla, and then the mother of Romulus:

All these were painted on the other side,

And all their love, and in what way they died.

When I had come again unto the place

Of which I spoke, that was so sweet and green,

Forth I walked to bring myself solace.

Then was I aware, there sat a queen:

As in brightness the summer sun’s sheen

Outshines the star, right so beyond measure

Was she fairer too than any creature.

And in a clearing on a hill of flowers

Was set this noble goddess, Nature;

Of branches were her halls and her bowers

Wrought according to her art and measure;

Nor was there any fowl she does engender

That was not seen there in her presence,

To hear her judgement, and give audience.

For this was on Saint Valentine’s day,

When every fowl comes there his mate to take,

Of every species that men know, I say,

And then so huge a crowd did they make,

That earth and sea, and tree, and every lake

Was so full, that there was scarcely space

For me to stand, so full was all the place.

And as Alain, in his Complaint of Nature,

Describes her array and paints her face,

In such array might men there find her.

So this noble Empress, full of grace,

Bade every fowl to take its proper place

As they were wont to do from year to year,

On Saint Valentine’s day, standing there.

That is to say, the birds of prey on high

Were perched, then small fowls without fail,

That eat, as Nature does them so incline,

Worms, or things of which I’ll tell no tale.

And waterfowl sat lowest in the dale;

But fowl that live on seeds sat on the green

So many there it was a wondrous scene.

There might men the royal eagle find

Who with his keen glance pierces the sun,

And other eagles of a lesser kind

On which scholars love to run.

There was the tyrant with his feathers dun

And grey – I mean the goshawk, who’ll distress

Others with his outrageous greediness.

The noble falcon, who with his feet will strain

At the king’s glove; sparrow-hawk sharp-beaked,

The quail’s foe; the merlin that will pain

Himself full oft the lark for to seek;

There was the dove with her eyes meek;

The jealous swan, that at his death does sing;

The owl too, that portent of death does bring;

The crane, the giant with his trumpet-sound;

The thief, the chough; the chattering magpie;

The mocking jay; the heron there is found;

The lapwing false, to foil the searching eye;

The starling that betrays secrets on high;

The tame robin; and the cowardly kite;

The rooster, clock to hamlets at first light;

The sparrow, Venus’ son; the nightingale,

That calls forth all the fresh leaves new;

The swallow, murderer of the bees hale

Who make honey from flowers fresh of hue;

The wedded turtledove with her heart true;

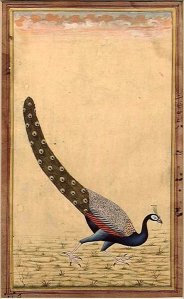

The peacock with angelic feathers bright;

The pheasant, scorner of the cock by night;

The wakeful goose; the cuckoo all unkind;

The parrot cram full of lechery;

The drake, destroyer of his own kind;

The stork, avenger of adultery;

The cormorant hot for gluttony;

The raven wise; the crow, the voice of care;

The thrush old; the wintry fieldfare.

What can I say? Fowl of every kind

That in this world have feathers and stature,

Men might in that place assembled find

Before the noble goddess Nature,

And each of them took care, every creature,

With a good will, its own choice to make,

And, in accord, its bride or mate to take.

But to the point: Nature had on her hand

A female eagle, of shape the very noblest

That ever she among her works had found,

The most gracious and the very kindest;

In her was every virtue there expressed

So perfectly Nature herself felt bliss

In gazing at her and her beak would kiss.

Nature, deputy of the almighty Lord,

Who hot, cold, heavy, light, moist and dry

Has knit in balanced measure in accord,

In gentle voice began to speak and sigh,

‘Fowl, heed my judgement now, pray I,

And for your ease, in furthering of your need,

As fast as I can speak, I will you speed.

You know that on Saint Valentine’s day,

By my statute and through my governance,

You come to choose – and then fly your way –

Your mates, as I your desires enhance.

But nonetheless my rightful ordinance

I may not alter, for all the world to win,

That he that is most worthy must begin.

The male eagle, as you all must feel,

The royal fowl, above you in degree,

The wise and worthy, secret, true as steel,

Whom I have formed, as you can see,

In every part as it best pleases me,

It needs not that his form I must portray,

He shall choose first, and speak in his own way.

And after him in order shall you choose

According to your kind, as you devise,

And, as your luck is, shall you win or lose;

But that one of you on whom love most lies,

God send him she that sorest for him sighs.’

And therewithal the eagle she did call,

And said: ‘My son, the choice on you does fall.

But nonetheless, bound by this condition

Must be the choice of everyone that’s here,

That she shall yet agree to his decision,

Whoever it is that shall her mate appear;

This is our custom ever, from year to year;

And he who at this time would find grace,

At blessed time has come unto this place.

With head inclined, humble, without fear,

This royal eagle spoke and tarried not:

‘My sovereign lady, with no equal here,

I choose, and choose with will and heart and thought,

The female on your hand so finely wrought,

Whose I am all, and ever will serve her I,

Do what she please: to have me live or die.

Beseeching her of mercy and of grace,

As she that is my lady sovereign,

To let me die right now, here in this place.

For certain, I’ll not live long in such pain,

Since in my heart is bleeding every vein;

Having regard only for my truth,

My dear heart, for my sorrow show some ruth.

And if that I be found to her untrue,

I disobey, or am blindly negligent,

Boastful, or in time chase after new,

I pray to you, on me be this judgement,

That by these fowls I be all torn then,

The very day that she should ever find

I am false to her or wilfully unkind.

And since none loves her as well as me,

Though she never promised me her love,

Then she should be mine, in her mercy,

For I’ve no other claim on her to move.

For never, for any woe, shall I prove

Faithless to her, however far she wend;

Say what you wish, my tale is at an end.’

Just as the fresh, the red rose new

In the summer sunlight coloured is,

So from modesty all waxed the hue

Of the female when she heard all this;

She neither answered, nor said aught amiss,

So sore abashed was she, till Nature

Said: ‘Daughter, fear you not, I you assure.’

Another male eagle spoke anon,

Of lesser rank, and said: ‘This shall not be.

I love her more than you do, by Saint John,

Or at the least I love her as well as ye,

Serving her longer in my degree,

And if she should have love for long-loving,

To me alone they should the garland bring.

I dare state too, that if she finds me yet,

False, indiscreet, unkind, rebellious,

Or jealous, you may hang me by the neck!

And if I do not fulfil in service

As well as my wits can, this promise,

In all respects her honour for to save,

Take she my life, and all my goods I pray.’

A third male eagle answered so:

‘Now, sirs, you know we’ve little leisure here;

For every fowl cries out to fly, and go

Forth with her mate, or with his lady dear;

And Nature herself would rather not hear,

By tarrying here, half that I would sigh;

Yet unless I speak, I must for sorrow die.

Of long service I may offer nothing,

Yet it’s as possible for me to die today

For woe, as he that has been languishing

These twenty winters, and happen it may

That a man may serve better and more repay

In half a year, although it were no more,

Than some man does who has served a score.

I say this not for myself, since I can

Do no service that may my lady please;

But, I dare state, I am her truest man

And, in my opinion, best seek her ease;

Briefly to speak, till death does me seize

I will be hers, whether I wake or wink,

And true in all that heart may bethink.’

In all my life since the day I was born,

So noble a plea in love or anything

Never heard any man but me before,

As would be clear if any had the cunning

And leisure to echo their way of speaking;

And from the morning did their speech last

Till downward went the sun wondrous fast.

The cries of fowls, now, to be delivered

Rang out so loud: ‘Have done, and let us wend!’

That I thought all the woods to pieces shivered.

‘Come on!’ they cried, ‘Alas, you us offend!

When will your cursed pleading have an end?

How should a judge for either party move

A yea or nay, without a shred of proof?’

The goose, the duck, and the cuckoo also

‘Kek, kek!’ ‘Cuckoo!’ ‘Quack, quack!’ cried so high

That through both ears the noise did flow.

The goose said: ‘All this is not worth a fly!

But find a remedy thereof can I,

And I will give my verdict fair and swiftly

For water fowl, whoever’s pleased or angry.’

‘And I for worm-eaters,’ said fool cuckoo,

For I will on my own authority,

For the public good, take up the charge now,

Since to free us quickly is great charity.’

‘You must abide a while yet, indeed!’

Said the turtle-dove,’ If it’s your will

That one may speak, who’d better shut his bill.’

I’m a seed-eater, one of the un-worthiest,

As I well know, and little own to learning;

But better it is a creature’s tongue rest

Than that he meddle in those doings

Of which he can neither speak nor sing.

And he who does so, his cause destroys,

For a service not requested oft annoys.’

Nature, who had always kept an ear

On the foolish murmuring behind,

With eloquent voice said: ‘Hold your tongues there!

And I shall soon, I hope, a method find

To release you, and from this noise unbind;

I decree that every group on one shall call

To announce the verdict for you all.’

Agreeable to this same conclusion

Were all the fowls: and the birds of prey

Chose the first by open election,

The male falcon to speak out and say

All their judgements, and adjudicate;

And, to Nature, himself he did present,

And she accepted him with glad intent.

The eagle spoke then in this manner:

‘It were full difficult to prove by reason

Who loves best this noble female here;

Each so puts forward his justification

That none by argument may be beaten.

I cannot see that arguments avail;

Then by battle it seems one must prevail.’

‘We’re ready!’ the male eagles quoth anon.

‘Nay, sirs! quoth he, ‘If I may dare to say,

You do me wrong, my tale is not yet done!

For sirs, take no offence of me I pray,

It may not, though you wish, happen this way;

Ours is the voice whose decision is at hand,

And the judge’s judgement you must stand;

And therefore, peace! I say, so works my wit,

That to me it seems that the worthiest

In knighthood, who’s longest practiced it,

Highest in rank, and of blood the noblest,

Were most fitting for her, if she so wished;

And of these three she herself knows, also

Which that one is, since easy ‘tis to know.’

The waterfowl had all their heads laid

Together and, after short argument,

When each of them had his large mouthful said,

Agreed truly, by mutual assent,

That the goose, who was so eloquent,

‘Who so yearns to pronounce what we agreed,

Shall tell our tale,’ and prayed her God speed.

And, for these water fowl, then began

The goose to speak, and in her cackling

She said: ‘Peace! Now take heed every man

And hear the judgement I shall forth bring;

My wit is sharp, I hate all tarrying;

I advise him, though he were my brother,

Unless she loves him, let him love another!’

‘Lo, here’s a reason fitting for a goose!’

Quoth the sparrow-hawk, ‘Never prosper she!

Lo such it is to have a tongue that’s loose!

Now, by God, fool, it were better for thee

To have held your peace, than show stupidity!

It lies not in his wit, nor in his will,

But true it is, “a fool’s tongue’s never still.”’

Laughter arose from the noble fowls all,

And anon the seed-eaters chosen had

The turtle true, and to them her did call,

And prayed her to tell the plain truth

Of the matter, and say what she would do;

And she answered that plainly her intent

She would speak and truly what she meant.

‘Nay, God forbid that a lover should change,’

The dove said, and blushed for shame all red,

‘Though his lady evermore seem estranged,

Yet let him serve her ever till he be dead.

For truly, I praise not what the goose has said,

For though she died, no other mate I’d take,

I would be hers till death my end should make.’

‘A fine jest,’ quoth the duck, ‘by my hat!

That men should love forever causeless,

Who can find reason or wit in that?

Dances he merrily who is mirthless?

Who cares for him who couldn’t care less?’

‘Quack ye,’ quoth yet the duck, ‘full well and fair!

There are more stars above than just one pair!’

‘Shame on you, churl!’ quoth the noble eagle,

‘Out of the dunghill come the words you cite.

You cannot see whatever is done well.

You fare in love as owls do in the light;

The day blinds them though they see by night.

Your kind is of so low a wretchedness

That what love is, you cannot see or guess.’

Then the cuckoo did the moment seize

For the worm-eating fowls, and did cry:

‘So long as I may have my mate in peace,

I care not how long you all may strive.

Let both of them stay single all their lives!

This I advise, since there’s no agreeing;

This short lesson does not bear repeating.’

‘Yea, so the glutton gets to fill his paunch,

Then all is well!’ said the merlin for one;

‘You murderer of the sparrow on the branch,

Who brought you forth, you wretched glutton!

Live you single then, worms’ destruction!

Useless even the defects of your natures;

Go you ignorant while the world endures!’

‘Now peace,’ quoth Nature, ‘I command here!

Since I have heard all your opinions,

And in effect our end is yet no nearer;

Finally now this is my own conclusion:

That she herself shall make her own decision

Choose whom she wish, whoe’er be glad or angry,

Him that she chooses, he shall have her as quickly.

For since it may not here resolved be

Who loves her best, as said the eagle yet,

Then will I grant her this favour, that she

Shall have him straight on whom her heart is set,

And he’ll have her whom his heart can’t forget.

This I decide, Nature, for I may not lie;

To naught but love do I my thought apply.

But as for advice in what choice to make,

If I were Reason, then would I

Advise that you the royal eagle take,

As said the eagle there most skilfully,

As being the noblest and most worthy,

Whom I wrought so well for my pleasure;

And that to you should be the true measure.’

With fearful voice the female gave answer,

‘My rightful lady, goddess of Nature,

Truth it is, your authority I am under

As is each and every other creature,

And must be yours while my life endure,

And therefore grant me my first boon,

And my intent I will reveal right soon.’

‘I grant it you,’ quoth she, and right anon

The female eagle spoke in this degree,

‘Almighty queen, until this year be done

I ask a respite to think carefully,

And after that to make my choice all free.

This is the sum of what I’d speak and say;

You’ll get no more although you do me slay.

I will not serve fair Venus nor Cupid

In truth, as yet, in no manner of way.’

‘Now since there is no alternative,’

Quoth Nature, ‘there is no more to say;

Then wish I that these folks were away

Each with its mate, not tarrying longer here’ –

And spoke to them as you shall after hear.

‘To you I speak, you eagles,’ quoth Nature,

‘Be of good heart and serve you, all three;

A year is not too long to endure,

So each of you take pains in his degree

To do well; for, God knows, free is she

Of you this year; whatever may then befall,

This same delay is served upon you all.’

And when this task was all brought to an end,

Each fowl from Nature his mate did take

In full accord, and on their way they went.

And, Lord, the blissful scene they did make!

For each of them the other in wings did take,

And their necks round each other’s did wind,

Thanking the noble goddess, kind by kind.

But first were fowl chosen for to sing,

As was ever their custom year on year

To sing out a roundel at their parting

To do Nature honour and bring cheer.

The tune was made in France, as you may hear;

The words were such as here you’ll find

In the next verse, I have now in mind.

‘Now welcome summer, with your sun soft,

That this winter’s weather does off-shake,

And the long nights’ black away does take!

Saint Valentine, who art full high aloft –

Thus sing the small fowls for your sake –

Now welcome summer, with your sun soft,

That this winter’s weather does off-shake.

Well have they cause to rejoice full oft,

Since each a marriage with its mate does make;

Full joyous may they sing when they wake;

Now welcome summer, with your sun soft,

That this wintry weather does off-shake,

And the long nights’ black away does take.’

And with the cries, when their song was done,

That the fowls made as they flew away,

I woke, and other books to read upon

I then took up, and still I read always;

I hope in truth to read something someday

Such that I dream what brings me better fare,

And thus my time from reading I’ll not spare.

End of the Parliament of Fowls

Translated by A. S. Kline © 2007

You must be logged in to post a comment.